even if you are not an Economics concentrator, Social Analysis 10 (i.e., Ec 10) is a good bet for some useful knowledge, as Bush-lover Greg Mankiw has made the problem sets and exams much more straightforward and manageable. You also never know if you are going to apply for that job with Morgan Stanley.

Thursday, August 31, 2006

Advice for Harvard Students

Cutler on Health Spending

By the way, David will once again give a lecture on health economics this fall in ec 10.Study Finds Health Care Good Value Despite Costs

The dramatic increase in health-care spending in the United States since 1960 is a major reason that Americans are living longer, making the world's most expensive health-care system a good value despite its high costs, according to an academic study being released today.

The study notes that a baby born in 2000 can expect to live for 76.9 years, compared with 69.9 years for a newborn in 1960. While some of the gain is because of declines in rates of smoking and fatal accidents, it is reasonable to attribute at least half of it to more and better health care, said Harvard University economist David M. Cutler, the study's lead author.

Are long-term jobs disappearing?

For some years it has been that reported that employees in the United States experienced widespread, substantial declines in job security or stability over the past several decades. Various newspaper articles have suggested that big structural changes in labor markets mean that job security is a "myth," that lifetime employment with a single employer is far less likely than it was, say, thirty years ago. Workers themselves worry that their prospects for keeping a job for a long period have shrunk, that they may need several jobs during their careers. "There is, however, a striking lack of solid empirical evidence to support these claims," writes economist Ann Huff Stevens.

In The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same: Trends in Long-Term Employment in the United States, 1969-2002 (NBER Working Paper No. 11878),Stevens sees stability in the prevalence of long-term employment for men in the United States, contrary to popular views. "Long-term relationships with a single employer are an important feature of the U.S. labor market in 2002, much as they were in 1969," she writes. So, the likelihood is that most workers will have some job during their working lives that lasts for more than 20 years.

Stevens uses data from surveys of men aged 58-62 who were quizzed at the end of their working careers. She finds that in 1969 the average tenure for men in the job they held for the longest period during their careers was 21.9 years. In 2002, the comparable figure was 21.4 years, not much different. Just more than half of men ending their careers in 1969 had been with a single employer for at least 20 years; the same was true in 2002.

From the September 2006 NBER Digest.

Update: Loyal reader mvpy calls attention to lecture notes in which superstar MIT economist Daron Acemoglu makes a similar point. Here is Daron:

there is basically no evidence for greater churning in the labor market. First, measures of job reallocation constructed by Davis and Haltiwanger indicate no increase in job reallocation during the past 20 or so years. Second, despite the popular perception to the contrary, there has not been a large increase in employment instability. The tenure distribution of workers today looks quite similar to what it was 20 years ago. The major exception to this seems to be middle-aged managers, who may be more likely to lose their jobs today than 20-25 years ago.

Daron's lecture notes on "Technology and the Structure of Wages" look like they are well worth reading in their entirety--all 154 pages of them!

Wednesday, August 30, 2006

California tackles global warming

Based on the article (and a similar one at the Washington Post), the proposed new system for carbon emissions appears to be exactly the sort of pollution permit market discussed in chapter 10 of my Principles text and which economists have long endorsed.I took Econ 110 here at BYU over the Summer and we used your excellent book (Principles of Economics) as the text for our class. It is probably one of the very few texts that I will be keeping around with me as I graduate and move on.

On a less "brown-nosing note" I thought you might be interested in this article from the Guardian regarding California and Arnold's deal with the Dems to create an exchange for companies to buy/sell/trade pollution permits; they call them emission credits... same thing. I guess my home state (one of the most polluted) is finally coming around and smelling the roses... or at least making it possible for everyone else to smell them! :-)

The article does not say how these permits would be allocated. Ideally, they would be sold. A sale provides the government nondistortionary revenue that can be used to reduce distortionary taxes. If that is the case, I will make Arnold honorary president of the Pigou Club.

In many similar cases, however, the permits are given out for free to established firms. This is surely second-best from the standpoint of economic efficiency. And it is questionable on the grounds of equity: Why should established polluters get a free ride while future polluters have to pay for the right?

News for Emily Litella

The NY Times two days ago in a front-page, above-the-fold article:

wages and salaries now make up the lowest share of the nation�s gross domestic product since the government began recording the data in 1947.The NY Times online today, presumably to be reported in tomorrow's paper (on what page? [update: page C1]):

As Emily Litella would say, "Never mind."Perhaps the biggest surprise in today�s report was a surge in wage-and-salary income during the first half of this year. Between the fourth quarter of last year and the second quarter of 2006, it grew at an annual rate of about 7 percent, after adjusting for inflation, up from an earlier estimate of 4 percent, according to MFR, a consulting firm in New York.

As a result, wages and salaries no longer make up their smallest share of the gross domestic product since World War II. They accounted for 46.1 percent of economic output in the second quarter, down from a high of 53.6 percent in 1970 but up from 45.4 percent last year.

Total compensation � including employee health benefits, which have risen in value in recent years � equaled 57.1 percent of the economy, down from 59.8 percent in 1970. Still, compensation makes up a larger share of the economy than it did throughout the 1950�s and early 60�s, as well as during parts of the mid-1990�s and the last couple of years.

Update: My friend Jason Furman emails me his observations on the matter:

Greg,

Measured properly wages and salaries in the first half of 2006 were the lowest as a share of economy since WW II.

The proper denominator for factor shares is gross domestic income (GDI) or national income. Using either denominator, wages and salaries are the lowest since World War II. CEA's Economic Report of the President always shows incomes as a fraction of GDI as does NIPA Table 1.11.

You are correct that as a share of gross domestic product (GDP) wages and salaries are no longer the lowest since WW II. But this is an apples-to-oranges comparison -- which is why neither the very careful CEA nor the very careful BEA would do it. (It is, alas, a common practice to use GDP in the denominator -- one that many excellent economists and reporters, including the New York Times -- follow.)

Specifically, the statistical discrepancy between GDP and GDI shows up in the denominator but not in the numerator. In 2006-Q2, GDP was $76 billion lower than GDI. If you're using GDP in the denominator, then this $76billion should be subtracted from some combination of wages, profits, rents, etc. Conversely, in 2005 GDP was $71 billion higher than GDI. As a result, to use GDP in the denominator you should also add this $71 billion to incomes.

Since we don't know how the statistical discrepancy breaks out between different factor incomes (that's why it's a "statistical discrepancy") we use GDI in the denominator. Or to avoid screwy results from depreciation, I generally prefer to use national income. Either way, the Times headline holds up.

Best, Jason

P.S. I should say I'm not that interested in wage shares, compensation shares are the relevant metric for most important questions. And the upward revision in wages certainly is a good sign and helps make sense of the revenue surprises we experienced this year -- and might suggest they'll be somewhat more durable than the potentially more ephemeral capital gains and corporate profits. But since you were being picky, I thought you might as well help your Ec 10 students to learn some national accounting arcana.

Blurb from Brad

Certainly the clearest introductory macro book.Now I just have to figure out how to convince Brad to order it for his course at Berkeley, rather than using the book by DeLong and Olney.

Rogoff on World Trade and Central Banking

one should think of the modern era of rapidly expanding trade and technology progress as providing a spectacularly favourable milieu for monetary policy. With hugely positive underlying trends, central banks have been able to establish and maintain low inflation while delivering growth results that have often outperformed expectations.... But precisely because globalisation has produced such a steady stream of upward surprises, there is an element of illusion to central banks� success.

Tuesday, August 29, 2006

Ranking Economics Papers

First, the winners:

The Most Cited Paper is Hal White's "A Heteroskedasticity-Consistent Covariance-Matrix Estimator and a Direct Test for Heteroskedasticity," Econometrica 1980, with 4318 citations in the Social Science Citation Index.

Next comes Kahneman and Tversky's 1979 article on "Prospect Theory - Analysis of Decision under Risk," Econometrica 1979, with 4085 cites.

In third place is Jensen and Meckling's "Theory of Firm - Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure," Journal of Financial Economics, 1976, with 3923 cites.

Next, the reliable home run hitters:

Only 146 journal articles published since 1970 have been cited more than 500 times. Within these 146 articles, an elite group of 11 economists authored or co-authored at least three. Robert Barro, Eugene Fama, and Joseph Stiglitz have six each. Michael Jensen follows with five; Robert Lucas and David Kreps with four; and Robert Engle, Lars Hansen, Robert Merton, Edward Prescott, and Stephen Ross have three each.

Finally, some naked self-promotion:

The author of this blog has one paper on the list, coauthored with David Romer and David Weil. Our paper, "A Contribution to the Empirics of Economic Growth" in the Quarterly Journal of Economics 1992, has 792 citations and is ranked number 65.

When I was writing this paper, I had no idea that it would become my most cited work.

Which inflation rate?

Even though many economists endorse some form of inflation targeting, there is no consensus about how inflation is best measured for purposes of such a policy. The Fed's tradition of focusing on a consumption deflator excluding food and energy is plausible, but it is only one of many plausible choices. As far as I know, this particular choice has never been fully justified over others. Some members of the FOMC may share Charlie's judgment on this question.The US Federal Reserve is wrong to focus on core measures of inflation that exclude energy prices, Charles Bean, chief economist at the Bank of England, has suggested. It should focus instead on headline inflation, which is much higher, he argued. Including energy and food costs, US consumer price inflation is running at an annual rate of 4.1 per cent, against 2.7 per cent for core inflation.

Mr Bean told the Fed�s annual Jackson Hole symposium at the weekend that energy prices were rising for the same reason the price of many manufactured goods were falling: the rise of China and other emerging market economies. Since both price trends had a common cause, he said it makes little sense to focus �on measures of core inflation that strip out energy prices while not stripping out falling goods prices as well.�

The bottom line: This is yet another reason to think that for the foreseeable future the Bernanke Fed's commitment to inflation targeting is likely to be vague and informal. Monetary policy will remain more discretionary than rule-based.

Update: A reader calls to my attention an August 29 speech by Dallas Fed President Richard Fisher in which he addresses the issue:

In preparing for our deliberations at the FOMC, I have come to rely upon what is called the Trimmed-Mean PCE Deflator....The business of getting it right on inflation is not an easy task. I keep a close eye on all of the inflation measures.This statement can be seen as further confirmation that there is no consenus on which price index to use. Until monetary policymakers settle on a price index, inflation targeting cannot possibly become the rule-based monetary policy that some people would like it to be.

How are wages and productivity related?

Economic theory says that the wage a worker earns, measured in units of output, equals the amount of output the worker can produce. Otherwise, competitive firms would have an incentive to alter the number of workers they hire, and these adjustments would bring wages and productivity in line. If the wage were below productivity, firms would find it profitable to hire more workers. This would put upward pressure on wages and, because of diminishing returns, downward pressure on productivity. Conversely, if the wage were above productivity, firms would find it profitable to shed labor, putting downward pressure on wages and upward pressure on productivity. The equilibrium requires the wage of a worker equaling what that worker can produce.

Why don�t real wages and productivity always line up in the data? There are a several reasons:

1. The relevant measure of wages is total compensation, which includes cash wages and fringe benefits. Some data includes only cash wages. In an era when fringe benefits such as pensions and health care are significant parts of the compensation package, one should not expect cash wages to line up with productivity.

2. The price index is important. Productivity is calculated from output data. From the standpoint of testing basic theory, the right deflator to use to calculate real wages is the price deflator for output. Sometimes, however, real wages are deflated using a consumption deflator, rather than an output deflator. To see why this matters, suppose (hypothetically) the price of an imported good such as oil were to rise significantly. A consumption price index would rise relative to an output price index. Real wages computed with a consumption price index would fall compared with productivity. But this does not disprove the theory: It just means the wrong price index has been used in evaluating the theory.

3. There is heterogeneity among workers. Productivity is most easily calculated for the average worker in the economy: total output divided by total hours worked. Not every type of worker, however, will experience the same productivity change as the average. Average productivity is best compared with average real wages. If you see average productivity compared with median wages or with the wages of only production workers, you should be concerned that the comparison is, from the standpoint of economic theory, the wrong one.

4. Labor is, of course, not the only input into production. Capital is the other major input. According to theory, the right measure of productivity for determining real wages is the marginal product of labor--the amount of output an incremental worker would produce, holding constant the amount of capital. With the standard Cobb-Douglas production function, marginal productivity (dY/dL) is proportional to average productivity (Y/L), which is what we can measure in the data. (See Chapter 3 of my intermediate macro text for a discussion of the Cobb-Douglas production function.) Keep in mind, however, that the Cobb-Douglas assumption of constant factor shares is not perfect. In recent years, labor�s share in income has fallen off a bit. (Between 2000 and 2005, employee compensation as a percentage of gross domestic income fell from 58.2 to 56.8 percent.) From the Cobb-Douglas perspective, this means that the marginal productivity of labor has fallen relative to average productivity. This modest drop in labor�s share is not well understood, but its importance should not be exaggerated. The Cobb-Douglas production function, together with the neoclassical theory of distribution, still seems a pretty good approximation for the U.S. economy.

Update: If you want to look at data on factor income shares, go to the BEA. Click on "List of All NIPA Tables." Then click on Table 1.11. You can then judge for yourself whether the changes in income shares are large or small.

Update 2: Economists Russell Roberts and David Altig also blog on this topic.

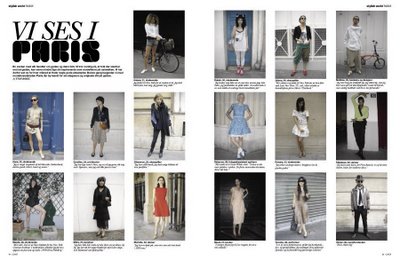

my first "stylish world" column in COVER magazine (september issue)

Monday, August 28, 2006

Ranking Economists

Answer:

Number one is Joe Stiglitz.

Number two is Martin Feldstein.

The author of this blog is number 146.

My excuse: I wasn't born until 1958.

Thanks to Division of Labor for the pointer.

Collier on Africa

Paul Collier of Oxford University made a persuasive case that nowhere more than in Africa has geography undermined economic progress. Statistically, a country�s growth is more likely to lag if it is landlocked, resource-poor or small, and Africa, which is divided into over 40 countries, has an unusually large number of countries that are all three.

Many African countries are resource rich but are unable to efficiently spend those resources because, while democratic, they lack effective checks and balances. By contrast, countries that must rely on taxes are more likely to face demands for accountability. African countries, despite being small, are also ethnically diverse. The more diverse a society, the smaller the share of the population represented by the ruling group, he notes. �A minority in power has an incentive to distribute to itself at the expense of the public good of national economic

growth.�Finally, he says, Africa has missed the globalization boat: at the time Asia was opening up to foreign investment, Africa was saddled with overvalued currencies, civil war, experiments with socialism, or apartheid. Almost all these problems have been solved, but in the meantime Asia has acquired a formidable critical mass of local skills and infrastructure that make it difficult for Africa to compete for foreign investment....

�African performance has been far worse than that of any other region,� Mr. Collier has written. �The explanation for this is not that African economic behavior is fundamentally different from elsewhere, but rather that African geographic endowments are distinctive.�

He sharply disagreed with economist-celebrity Jeffrey Sachs�s view that disease and climate are the principal reasons for Africa�s underdevelopment. Sachs, he said, is �barking up the wrong tree.�

Mallaby on the New Democratic Party

Once upon a time, smart Democrats defended globalization, open trade and the companies that thrive within this system. They were wary of tethering themselves to an anti-trade labor movement that represents a dwindling fraction of the electorate. They understood the danger in bashing corporations: Voters don't hate corporations, because many of them work for one.

Then dot-bombs and Enron punctured corporate America's prestige, and Democrats bolted. Rather than hammer legitimately on real instances of corporate malfeasance -- accounting scandals, out-of-control executive compensation and the like -- Democrats swallowed the whole anti-corporate playbook.

A New Job for Jeff

This gets me thinking about who might fill various roles during the administration. Bono for veep? Angelina Jolie for Secretary of State? Brad DeLong for Press Secretary? Bill Easterly for the loyal opposition?

One thing I'm sure of is that Jeff's wife, Sonia, would make a great first lady.

Sunday, August 27, 2006

A Joke for Econ Grad Students

Pointer from student Gabriel Mihalache, who remarks: "I don�t know what�s more perverse...that I understand the joke or that I find it really funny."A group of macroeconomists are sitting on a panel at a conference discussing developments in the discipline.

In a heated exchange, the New Keynesian says to the Real Business Cyclist: �You guys have put macroeconomics back twenty years with this nonsense!�

The Real Business Cyclist smiles and says �So you DO believe in negative productivity shocks after all.�

Saturday, August 26, 2006

Warning: Advertisement

if you ever choose to take an economics class, make sure the professor assigns a textbook by Mankiw. I swear by this man, people. He is an amazingly good author, which is something 99f economists are NOT. I'm actually reading a different version of the book below (there are 5, i believe- mine is called ...um. wait, maybe it is this one) no.. its not, I don't really have time to look for the version i have but I do have a camera phone so I guess i can post my own picture... heheheh... that makes me feel clever. handy little phone. btw, I found my phone. in case you were wondering.oh- and the Xtra! thing--- so useful, the subscription lasts a year... very neato stuff, but if you're just reading it for your own interests, it not really necessary, its just alternative ways to tell you shit that may be hard to pick up on by reading, especially if math is not your strong point when it comes to economics.

Another one for the "I told you so" file

Study: Outsourcing Raises U.S. Wages

Two Princeton University economists claim that job outsourcing increased productivity and real wages for low-skilled U.S. workers.

Princeton professors Gene Grossman and Esteban Rossi-Hansberg debated that salaries for the least-skilled blue collar jobs had been increasing since 1997 as outsourcing pushed productivity....

The Princeton economists say that critics tended to gloss over the productivity benefits that come with offshoring labor.

Update: Here is the Grossman-Rossi-Hansberg paper.